Kashmir, often is renowned not only for its stunning landscapes and tranquil lakes but also for its rich legacy of handicrafts. For centuries, Kashmiri artisans have crafted exquisite masterpieces, preserving skills handed down through generations. From luxurious Pashmina shawls to intricately carved wooden artifacts, Kashmiri handicrafts embody the spirit of the region’s culture and craftsmanship.

The art of Kashmiri craftsmanship is more than just a livelihood; it’s a way of life. Each creation tells a story, reflecting the creativity and dedication of artisans who have perfected their skills over generations.

Kashmiri handicrafts are a traditional art of Kashmiri people and artisans who make, craft, and decorate objects by hand. Ganderbal and Budgam are the main districts in central Kashmir, which have been making handicraft products for ages. The rest of its districts, including Srinagar, Ganderbal, and Budgam, are best known for their cultural heritage, which includes the handicraft industry in Jammu and Kashmir, India.

Embroidery is an integral part of many Kashmiri handicrafts, shawls, carpets, and Kashmiri ladies’ pheran are adorned with intricate embroideries or flower styles made of thin metal threads, and this kind of embroidery is known as ‘Tille’ in the Kashmiri language. Embroidery work is done by both men in women in the region conventionally.

Historical Background of Kashmiri Handicrafts

Historical Craft Connections: Zain-ul-Abidin, the 9th Sultan of Kashmir (15th century), introduced Central Asian craft techniques to Kashmir with the help of artisans from Samarkand, Bukhara, and Persia. After his reign, these connections weakened and came to an end by 1947.

Located on the historic Silk Road, Srinagar became a melting pot of cultural, economic, and artistic exchanges. This cross-cultural interaction played a vital role in the development of Kashmir’s distinctive crafts.

- Kashmiri artisans, known for their intricate woodwork, adopted techniques from Central Asia.

- While Kashmiri woodcarvers used chisels and hammers for detailed designs, Iranian woodcarvers typically employed a single chisel for floral motifs.

- Kashmir’s carpet weaving was profoundly shaped by Persian techniques.

- The Persian knotting methods, including the Farsi baff and Sehna knots, were incorporated into Kashmiri carpets.

- Additionally, Kashmir’s carpet patterns are named after Iranian cities like Kashan and Tabriz, highlighting the cultural ties, with artisan exchanges further enhancing skills and inspiring craftsmanship.

- Uzbekistan’s suzani embroidery was recognized as a precursor to Kashmir’s sozini work. Similarities were observed in techniques, color palettes, and floral motifs.

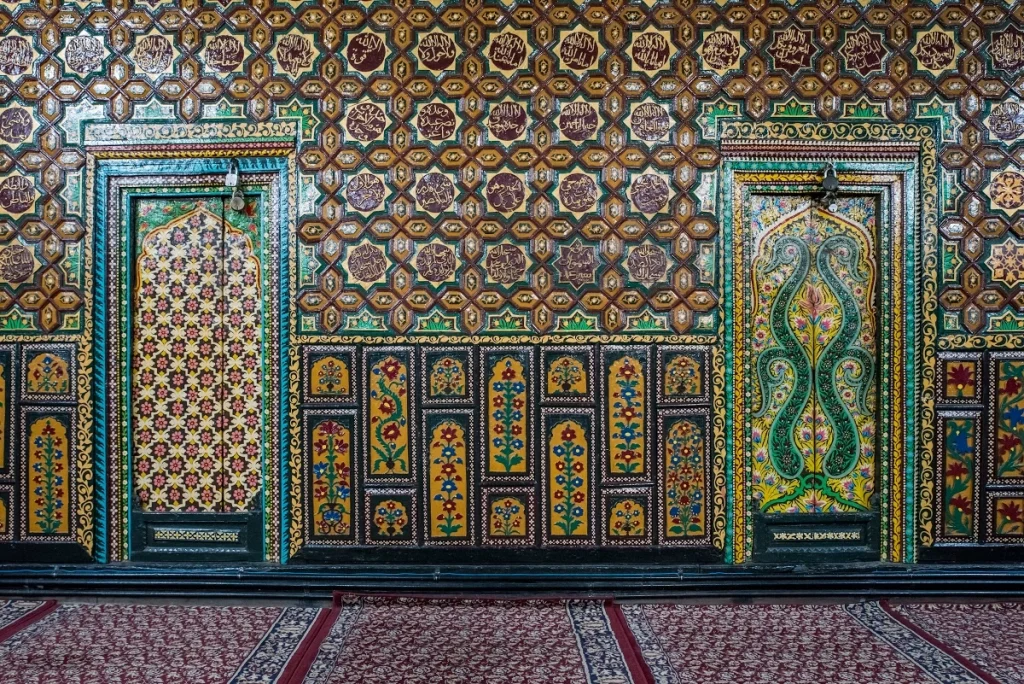

The inspiration for the creation of the arts and crafts of Kashmir is the paradisiacal land of Kashmir in its physical and metaphysical meaning and expression. The artistic genius of the Kashmiri people is expressed in the field of literature. Poetry, literary images, shawl-making, embroidery, embroidered floor-coverings, wood-work and wood-carving, papier-mache and metal-work have been studied by the author, in the beauty of their composition, history, making, and design movement.

The arts and crafts of Kashmir testify to the Kashmiri artist being a true lover of nature. Nature is reflected in the polished mirror of the designs and decorative patterns of ornamentation of the Kashmiri arts. Poetry in form to reach the realm of thought, idea, dream, and vision that shows joy in this world as the world is joyful in Him.

This can be understood through the analogy of the traditional carpet being the earthly reflection of the cosmos itself. Therefore, it follows that it is an indication, suggestion, or expression of the mirror image of the manifestation in worldly, material, mortal, and whatsoever is possible in the non-spiritual world or the secular world, the space, universe, or the heavens above, which are divine and sacred.

Importance of Handicrafts in Kashmiri Culture

Handicrafts are deeply ingrained in Kashmiri culture, serving as a major source of income and a vital means of preserving cultural heritage. They reflect the region’s rich history and artistic traditions, offering a tangible connection to the past and a way to showcase unique skills and creativity.

The handicraft sector is a significant employer, particularly in rural areas, and provides a livelihood for numerous families, including those with disabilities. It’s a labor-intensive industry that doesn’t require large capital investments, making it accessible to many.

Cultural Preservation

Handicrafts like Pashmina shawls, wood carvings, and carpet weaving represent centuries-old traditions and skills passed down through generations. They act as a visual language, showcasing the unique artistic heritage of Kashmir.

Artistic Expression

Kashmiri handicrafts are known for their intricate designs, fine quality, and unique artistry, reflecting the creativity and skill of local artisans.

Tourist Attraction

The beauty and uniqueness of Kashmiri handicrafts attract tourists, contributing to the local economy and further promoting the region’s cultural identity.

Social Significance

Handicrafts are not just about creating beautiful objects; they are also about fostering a sense of community and pride. They provide a space for artisans to share their knowledge and skills with others, and for families to connect with their cultural heritage.

Famous Kashmiri Handicrafts

Generations have passed down a tradition of exquisite craftsmanship in the heart of the Himalayas, where the air is filled with the aroma of saffron and the sound of traditional music. Kashmir is known for its handicrafts and cultural heritage. Each of the Kashmiri handicrafts reflects a story of the rich cultural heritage and skilled artisans of the region, making it a must-visit destination for art lovers. They weave magic into every thread, carve stories into every piece of wood, and write history into every piece of paper.

Pashmina Wool and Shawls

Pashmina shawls gained much prominence in the days of the Mughal Empire as objects of rank and nobility. Babur first established the practice of giving khilat – giving ‘robes of honour’ – in 1526 to members of his court for their devoted service, high achievements, or as a mark of royal favour. A khilat could be a set of clothes consisting of a turban, coat, gown, trousers, shirts, etc., all of which could be made of Pashmina wool.

Upon the complete conquest of Kashmir in 1568 by Akbar, a pair of pashmina shawls was an integral part of a khilat ceremony. Other emperors of the time, such as the Safavid and Qajars, also wore and gifted pashmina shawls within their political circles.

Pahsmina shawls and blankets were indicators of wealth and part of a rich woman’s dowry in India, Nepal, and Pakistan. These shawls acquired the status of heirlooms that would be inherited instead of being purchased, as it was considered too expensive to buy. Through extensive trade with Indian, the shawls made their way to Europe, where they became an almost instant hit.

Every winter, the goats from whom pashmina is acquired shed their coat. About 80-170 grams of wool is shed. In the spring, the undercoat is shed, which is collected by combing the goat instead of shearing them, as is the case with other wool collection activities. The pashmina wool is produced by the people known as the Changpa, a nomadic people who inhabit the Ladakh region. The Changpa rear sheep in a harsh climate where the temperature drops to −40 °C.

Raw pashmina is exported to Kashmir, where the combing, spinning, weaving, and finishing are traditionally carried out by hand by a specialised team of craftsmen and women. The major production centre of pashmina shawls is in the old district of Srinagar. It takes about 180 hours to produce a single piece of pashmina shawl.

Kani shawls

Kani shawl is made from pashmina on a handloom. But instead of a shuttle used in regular pashmina shawls, Kani shawls use needles made from cane or wood. The distinguishable, Mughal patterns, usually of flowers and leaves, are woven into the fabric like a carpet, thread by thread, based on the coded pattern called ‘Talim’. The talim guides the weaver in the number of warp threads to be covered in a particular colored-weft. The Kani shawls are made from Pashmina Yarn.

It is considered that it is the best Shawl you can ever buy. The undercoat of the Pashmina Goats that they shed in the spring is naturally collected by the local artisans, is used to make the most expensive fabric on earth. The Changthangi goats that reside in the cold desert area of Ladakh grow an undercoat to sustain the temperature of winter (which goes up to -40° C) in the region.

Those soft hairs are separated and cleaned to prepare for yarn spinning. Then the artisans, mostly women, hand spin the hair to make the delicate Pashmina wool in their Charkhas. After making the yarn, it is time to weave the shawl. The difference from other Pashmina shawls with Kani Shawls starts from here. It does not use the shuttle like regular Pashmina weaving, but cane or wooden needles are used to weave it.

The designer is known as the naqash who creates the pattern of the shawl. In designing, a huge influence of the Mughal Era can be seen. It is quite similar to the flowers and leaves that are woven into the carpet. The naqash first draws the design on the graph paper and then fills it with colors.

The weavers are the craftsmen who bring the design to life with the help of the stick needles that are loaded with different colors of yarns. Surprisingly, there is no embroidery, but the design is woven into the texture of the shawl. That is the exclusiveness of it. Even no bobbin shuttles from one side to another to make the wrap. The needles that are called Tujis, with different colors of yarns, are inserted at different points of the thread spread.

Families who are weaving Kani Shawls usually work patiently, working between 5 and 7 hours a day, in between attending to their household chores. Depending on the intricacy and complexity of the design being woven, an artisan can weave a maximum of a few centimetres per day. Depending on the design, size, and detailing, a Kani Shawl may take anything between 6 and 18 months to be completed.

Papier Mache Art

Papier-mache, among these handicrafts, is an age-old craft that was introduced to the valley by Mir Sayyid Ali Hamadani, who arrived from Persia with skilled craftsmen in the 14th century. The Sufi Muslim Mir Sayyid Ali Hamadani, also addressed honorifically throughout his life as “Shah-e-Hamadan,” meaning “King of Hamadan,” was instrumental in spreading Islam in the region and introducing many crafts and industries to Kashmir.

With the advent of Islam, papier-mache became one of the core artistic professions, holding considerable religious relevance in the valley. It is one of the oldest handicrafts, which is deeply interwoven with the culture and tradition of Kashmiri society and whose legacy has been passed from one generation to another for centuries. Besides, it generates employment for hundreds and thousands of Kashmiri households. The locally manufactured papier-mache products are brought to local retail shops and tourist attractions for sale and are also exported to international markets, mainly in Europe.

Papier-mache is a French word that means chewed paper, and the process of making it involves two steps: Sakhtsazi and Naqashi. Sakhtasazi, the initial stage of preparation, includes the making of the figurine from the mixture of paper pulp with the help of rice straw and copper sulfate. In the final step of Naqashi, several coats of paint are applied, and the figurine is decorated. Artists prefer to use organic colors to paint their mesmerizing products. The entire procedure, which is done manually, requires much care and deliberation and is tedious and time-consuming.

Kashmiri Carpets

The Kashmiri Carpets are famous not only in India but across the globe. Kashmiri Carpet is known for its specialty of being handmade, and similarly, it is knotted and not tufted. The idea of carpets is nearly 1500 years old, and it is not exactly known where and by whom the first Carpet was made. However, in India, Carpet weaving was first introduced in Kashmir in the late 15th Century by King Budsha, who brought artisans from Persia to train the people in Kashmir to spin and weave Carpets.

Though the people of Kashmir were already introduced to weaving and spinning, the King insisted on their learning the technique from the Persians. The art of Carpet weaving in Kashmir is passed from one generation to another, and most of these traditional weavers prefer to hand weave the Carpets in spite of many new mechanized processes which have come up..

The process of Kashmiri Carpet making is quite laborious, for it involves a lot of time and different steps, starting right from the cultivation of silk or wool, treating and dyeing it, deciding the pattern of the carpet, weaving, and then adding the final touches.

Nakaash is the person who designs the Carpet, a Kalimba is the weaver, and the ranger is the person who dyes the Carpet in the local Kashmiri language. In the making of the Carpet, the weaver follows the Talim chart, which is a coded colour chart. This chart indicates the number of knots which has to be woven according to the planned colours. As the day starts, the master weaver reads out the code, and the assistants follow the instructions carefully.

Sozni and Ari Embroidery

Sozni (also known as Sozan Kaari) is a popular needlepoint embroidery technique from the Kashmir valley in Northern India. Kashmiri artisans have been practicing Sozni embroidery for almost 500 years. It’s mainly done in woolen and silk fabrics and is very famous for its use in Pashmina Cashmere shawls and jackets. The interesting fact about Sozni embroidery is that its intricacy can vary from 5 stitches per cm to 500 stitches per cm.

- Capturing the design on a tracing paper- The Naqash (Designer) makes the design on a tracing paper. The designs are created either by a senior embroidery kaarigar (craftsman) or by designers.

- Capturing design trace into carved wooden blocks- Once the trace is perfectly done, a wooden block is carved out to make blocks, which would be used to create imprints on the fabric.

- Filling the blocks with charcoal paste or chalk paste- The blocks are filled with either charcoal paste or chalk paste to impart black or white colour to the imprinted design.

- And then the Embroidery work starts- Once the design is imprinted on the fabric, the embroiderer uses a fine needle and thread to make the embroidery. The thread is usually of silk or a high-quality cotton. The main point to note here is that only the artisan who starts the embroidery finishes the embroidery, as embroidery making is just like handwriting, and the end result varies from person to person.

- Finishing- Once the embroidery is done, the shawl goes through cleaning and the final finishing process.

Aari embroidery is a traditional style of embroidery seen on Kashmiri dresses. The Aari practice is a very time-consuming process.

However, with the help of technology, the embroidery process has become quicker and easier. Aari work is executed using a hooked needle, Aari, which is placed under the fabric and is used to pull a chain of loops, each rising from the previous in continuous succession.

Products created through Ari work are stoles, shawls, pheran, kurta, and capes. This embroidery style started with a basic method of drawing designs on cloth and piercing holes along the lines of the design with a needle. The fine stitched patterns evolved into Aari work as an individual art form over time.

Wood Carving and Walnut Wood Furniture

Walnut wood carving is an ornamental and delicate craft process that is unique to Kashmir due to the concentration of walnut trees in this region.

Carved walnut woodwork is among the most important crafts of Kashmir. Kashmir is now one of the few places in the world where walnuts are still available at an altitude of 5500–7500 feet above sea level. The wood is hard and durable, its close grain and even texture facilitating fine and detailed work. It also presents visually interesting effects with mere plain polished surfaces.

The Kashmir craftsman rejoices in carving intricate and varied designs. A variety of carved products bear recurrent motifs of the rose, lotus, iris, bunches of grapes, pears, and chinar leaves. Dragon motifs and patterns taken from kani and embroidered shawls all find their place in wooden objects with deep relief carving.

Wood used for carving can be from the root or trunk of the tree. The wood derived from the root is almost black, with the grain more pronounced than the wood from the trunk. Branches have the lightest color with no noticeable grain. It is the dark part of the wood, which is best for carving, as it is strong. The value of the wood differs with the wood from the root being most expensive.”

Walnut trees are of four varieties. ‘Wantu’ or ‘Vont Dun’ (fruit has hard shell), ‘Dunu’ and ‘Kakazi’ or ‘Burzol’ (best fruit with lightest shell), which are cultivated, while the ‘Khanak’ is found in the wild. These can be cut only once they mature to give fruit.

The wooden planks so obtained are then numbered (dated) and piled one upon the other. The process is always carried out in the shade. The gaps between the different layers of the planks allow the passage of air, which helps in the seasoning process. Seasoning goes on for 1 to 4 years.

The naqqash, master carver, first etches the basic pattern onto the wood. And then removes the unwanted areas with the help of chisels. And a wooden mallet so that the design emerges from the lustrous walnut wood as an embossed surface.

The carving of furniture and smaller items is an elaborate process and involves a high degree of skill and craftsmanship.

Copperware (Kandkari)

Kashmir is a treasure trove of handicrafts, heritage, and natural beauty. Among the elegant treasures Kashmir possesses, Kashmiri copper works. Locally known as Kandkari works. Copper, locally known as tram, has been an indispensable commodity in Kashmir for ages. The age-old art of crafting copper works is deeply rooted in culture here and is famous all over the world.

The craftsmanship of Kashmir is known for the work of engraving and making household items. Decorative products like copper, including utensils like a pot, a Big plate, a water jug, a portable hand washing system, and the most famous Kashmiri Samovar. Copperware requires an ample amount of time and labour, and the making process is slow and difficult.

The process of making crafted copper items goes through many hands (Artisans), who are specialised in a particular technique. The process involves the smith (locally known as “Thanthor”). The engraves (locally known as “Nakash”). The gilder (locally as “Zarkood”). The polisher (locally known as “Roshengar”). The cleaner or finisher (locally known as “Charakgar”).

Namda and Gabba Rugs

Namdas: These are similar to miniature carpets but less costly than carpets. They are prepared from cotton or wool fibres, which are manually pushed into shape. Prices fluctuate with the percentage of wool. A Namda containing 30 per cent wool is less expensive than one that contains 75 per cent wool. Namdas are famous for their bright colours and attractive designs.

Gabba rugs: Gabba is finished from old woollens on which dissimilar colours cut out forms are held with chain stitches. The ends and the field are enclosed with hefty embroidery. These rugs are generally made of 65 percent wool or silk yarn and 35 percent cotton yarn. The bottom of the rug is hessian cloth in pastel colours and is backed by cotton cloth on the surface. Kashmiri needlework is done the motifs that are traditional Kashmiri floral patterns.

Role of Kashmiri Handicraft in the local economy

Handicrafts have a special socio-economic significance in J&K, keeping in view the vast potential in handicrafts for economic activities. Against an allocation of a mere Rs. 19.50 crore in 1974-75, the budgetary allocation for this sector has been increased to Rs. 24 crore during 1998-99.

Production of handicrafts crossed the Rs. 400 crore mark during 1998-99. There has also been a notable growth in the State’s exports in recent years. The traditional woollen shawls, papier-mache goods, wood-carvings, and carpets have all survived the onslaughts of many centuries of socio-economic evolution. The craft objects of Kashmir are ingrained in the socio-economic ethos of the people.

The State government has introduced two insurance schemes for the benefit of artisans. Schemes like Health & Group Insurance provide the facility of treatment and replacement of any defective organ of the artisan and Rs. 10,000 in case of death to the next of kin. Artisans have been brought within the ambit of the Cooperative Movement. As many as 873 craft cooperatives engaging over nine thousand craftspeople have been launched throughout the State.

Challenges Faced by Kashmiri Artisans

Kashmir is known for its vibrant and diverse artistic heritage, which has been passed down through generations of skilled artisans. However, these artisans face numerous challenges in today’s globalized and modernized world. Globalization and modernization on their own have had an impact on work. Kashmiri artisans have made their name worldwide for their skill. Producing a wide range of handicrafts, including shawls, carpets, papier-mache, and embroidery.

However, these traditional crafts are increasingly being threatened by competition from mass-produced goods and modern technology. One of the main challenges faced by Kashmiri artisans is the lack of infrastructure and support for their work. Many artisans work in small, home-based workshops without access to modern tools or resources. This makes it difficult for them to compete with large-scale producers who have access to modern machinery and technology.

In addition to these challenges, artisans are also faced with changing consumer preferences. Modern consumers are increasingly drawn to large-scale goods, which are cheaper and more readily available as compared to traditional handicrafts. This has made it difficult for traditional artisans to market their products and compete in the global marketplace.

Despite these challenges, there has been some success in the traditional artisan sector. Many artisans have adapted to techniques incorporating modern materials and designs, while still maintaining the traditional elements of their craft. Others have found success by focusing on niche markets, such as high-end luxury goods or eco-friendly products.

Conclusion

Handicraft is an integral part of the life of a Kashmiri, and social and technological changes are taking place. In other parts of the world, artisans are rich. And they create craft items that are considered to be luxury items. But in Kashmir, it is a major source of employment for a majority of the population, next to tourism.

In simple words, Handicrafts can be rightly defined as the products made by hand. Culture and tradition are the invisible part of the creator, and hence, culture and crafts are always intertwined. Kashmir’s rich cultural heritage is manifested by the wide array of handicrafts produced.

Leave a Reply